When I was researching my book, High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism, I was fascinated by how Hunter S. Thompson would read a word or phrase somewhere and then incorporate it into his own vocabulary. When you read his work, you see words like “doomed,” “savage,” and “atavistic” used over and over, but these weren’t always there. Looking at his letters, articles, and books, you can see when they began to appear and if you look at what he was reading around that time, you can often find those words in texts that were particularly influential on him.

Take “atavistic,” for example. It is certainly not a common word and yet Thompson used it frequently in his writing, so one might wonder when and where he acquired it. He is on record as saying he heard it in a bar in Ketchum, Idaho, when doing a story on the death of Ernest Hemingway. That might be true but Thompson was rarely honest about such matters. In fact, he first used it in that story but he did so after a paragraph that mentioned F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night. The word “atavistic” (or atavism) appears several times in that novel, which strongly suggests that it’s where Thompson encountered it.

The origins of “savage” are less obvious but Thompson first began using it in his writing when he was going through an obsession with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Around this time, he began making references to “Kubla Khan” and in that poem we find the phrase “A savage place!” Unlike “atavistic,” “savage” is hardly an uncommon word and Thompson may not have taken it from that poem, but given that it seems to have entered his vocabulary at the time he was calling himself “Cuubley Cohn” and living in a shack called “Xanadu,” one must wonder.

When you read Thompson’s work—and I mean every damn thing you can find, including letters—and then read the writers he was interested in at that time, you often see where he found his favourite words and phrases. The above examples stood out to me and you’ll find more of them in High White Notes, but there were some more challenging phrases that have proved harder to source. Let’s take a look at three particularly well-known ones.

Fear and Loathing

Thompson is on record as first using the phrase “fear and loathing” on November 22, 1963, in response to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. He wrote William Kennedy that “there is no human being within 500 miles to whom I can communicate anything – much less the fear and loathing that is on me after today’s murder.”

Was this a phrase he spontaneously created? He had been using “the Fear” (often capitalised) for a while but “fear and loathing” feels more like something he read and liked enough to borrow. The fact that he went on to use it so much suggests that he had made note of it in earlier reading. Douglas Brinkley gave an explanation in the book Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson:

Hunter used to claim that the phrase “Fear and Loathing” was a derivation of Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling. In actuality he lifted it from Thomas Wolfe’s The Web and the Rock. He had read the novel when he lived in New York. He used to mark up pages of favorite books, underlining phrases that impressed him. On page sixty-two of The Web and the Rock he found “fear and loathing” and made it his. I asked him why he didn’t give Wolfe credit. Essentially he said it was too much of a hassle, that people would think he meant Tom Wolfe, his New Journalism contemporary.

Is this true? It is not an unreasonable suggestion but in the recent publication Understanding Hunter S. Thompson, Kevin J. Hayes notes that “This conjoined word pair has a biblical feel” but notes that it does not appear in the Bible. He tracks its use over time, starting in 1646, but then makes a very interesting observation. After saying “Thompson could have encountered this idiomatic phrase practically anywhere,” he mentions that it appears in Lord of the Flies, a book Thompson had certainly read. (He reviewed another William Golding book a few months later and quite possibly was reading Lord of the Flies for the purpose of comparing these books in late 1963.) This is not definitive proof but I find it more likely than Brinkley’s explanation.

I reviewed Hayes’ book here:

Understanding Hunter S. Thompson (2025): A Review

A few weeks ago, Amazon alerted me to the release of a new book about Hunter S. Thompson. Part of the University of South Carolina’s Understanding Contemporary American Literature series, it is titled Understanding Hunter S. Thompson. To be brutally honest, I was a little reluctant to read it because I expected it to be the very opposite of what its tit…

Gonzo

The story about how Hunter S. Thompson came to be called a Gonzo journalist is well known. It dates back to the writing of “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved.” Thompson’s friend, the editor Bill Cardoso, read the article and called it “pure gonzo.” Thompson immediately adopted the word and began referring to his style of writing as “Gonzo.”

There is little debate over that, but where did Cardoso find this word? For the 20th anniversary of Thompson’s death, earlier this year, I decided to find out. There had been many theories, including a rather preposterous one from Brinkley, who said:

The Internet is full of bogus falsehoods propagated by uninformed English professors and pot-smoking fans about the etymological origins of “gonzo.” Here’s how it happened: The legendary New Orleans R&B piano player James Booker recorded an instrumental song called “Gonzo” in 1960. The term “gonzo” was Cajun slang that had floated around the French Quarter jazz scene for decades and meant, roughly, “to play unhinged.” The actual studio recording of “Gonzo” took place in Houston, and when Hunter first heard the song he went bonkers—especially for this wild flute part. From 1960 to 1969—until Herbie Mann recorded another flute triumph, “Battle Hymn of the Republic”—Booker’s “Gonzo” was Hunter’s favorite song. […] Later, when Hunter sent Cardoso his Kentucky Derby piece, he got a note back saying something like, “Hunter, that was pure Gonzo journalism!” Cardoso claimed that the term was also used in Boston bars to mean “the last man standing,” but Hunter told me that he never really believed Cardoso on this. Just another example of “Cardoso bullshit,” he said.

It is tempting to believe this, particularly after one of Thompson’s friends e-mailed me to confirm that Thompson had heard the song probably in 1960, but at the same time it is strange that Thompson never actually mentioned it in writing. He wrote often about songs and musicians he admired but there is nothing in any of his letters or articles about this one.

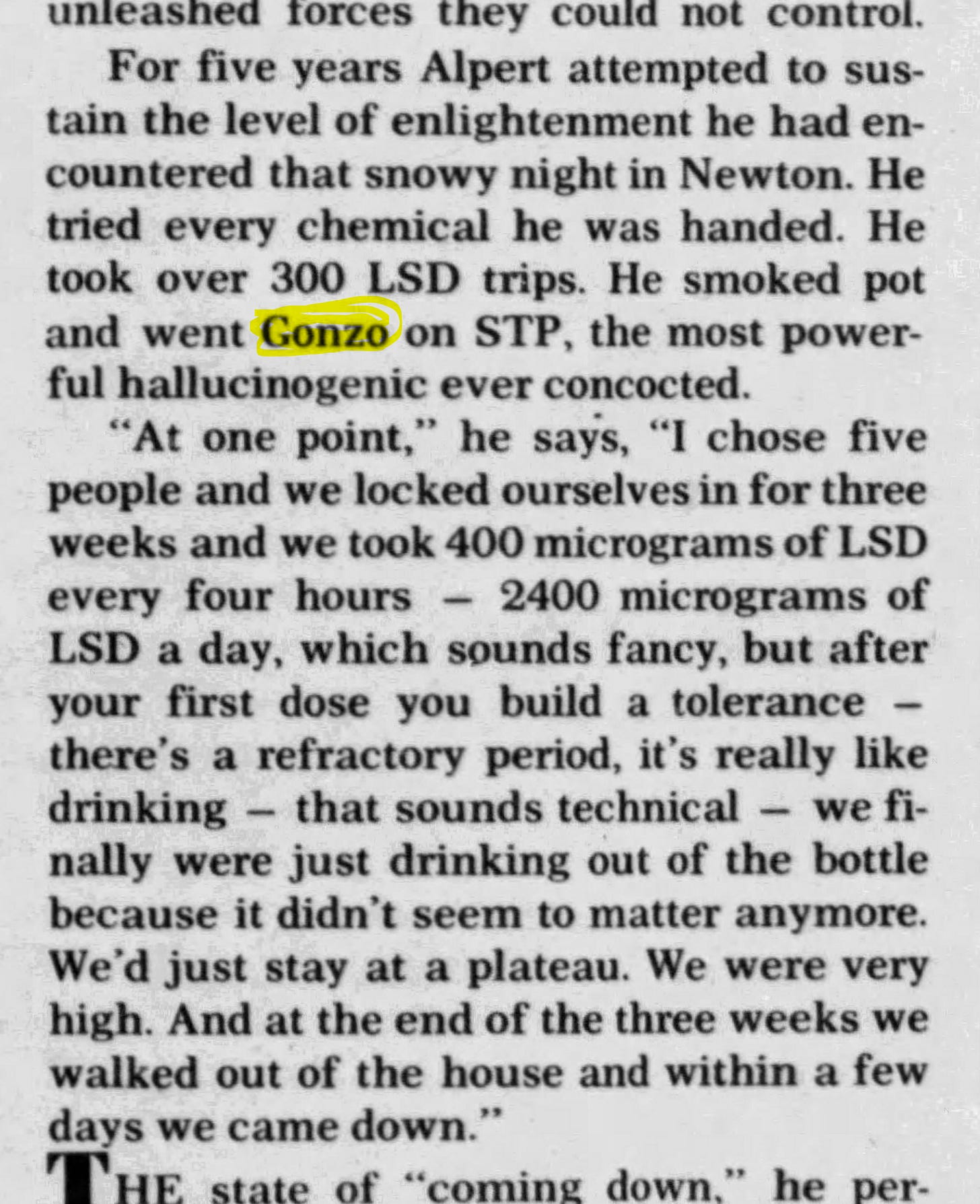

Fortunately, I managed to find a much more likely explanation. Bill Cardoso edited an article about Baba Dam Dass the same week that he wrote to Thompson calling his writing style “gonzo.” The article contained the phrase “went Gonzo on STP.” (STP was a hallucinogenic substance.) This is almost certainly where Cardoso first encountered it. If it was not his first encounter with the term “Gonzo,” then certainly it prompted him to write to Thompson. Given that the use of that word in this article meant “going wild on an intoxicant,” it seems a little too much to believe it was a coincidence.

You can read my full report on this, with much more evidence and discussion, here:

Raoul Duke

Let’s turn now to Thompson’s favourite pseudonym. Raoul Duke was his alter ego and a literary device he used often, starting in the late 1960s. As with the previous two words, there is some debate over where he found the name or when he invented it. Thompson has given several explanations and others have attempted the same. Douglas Brinkley once again had an explanation but his is objectively wrong. He claims Thompson invented the name after the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago but actually it had appeared in his writing since 1965. Biographer William McKeen said he’d been using it since his days at the Command Courier but this is also untrue. Thompson claimed he’d made it up as a tribute to Fidel Castro’s brother but he was joking and very frequently gave false explanations in order to confuse people and amuse himself.

The truth is most likely that he found the name in a newspaper article. Specifically, he seems to have read one of several articles about a Calgary businessman named Raoul “Duke” Duquette. These appeared during the time he was researching Hell’s Angels, at which point Thompson was reading newspapers from all across North America as part of his research.

Of course, Thompson would never admit that he’d found the name and borrowed it. He liked to create more exciting stories and hide the truth. However, the improbable name certainly appeared in print several times in places that Thompson was very likely to have seen it and it did so during a period when we know for sure he was looking at those sources. It seems to me fairly obvious that this is the origin of Raoul Duke.

You can read more about where Thompson found his favourite words and names in High White Notes. The book also pulls apart various myths and presents the true stories behind the often-fictionalised life of Hunter S. Thompson. I also show how he borrowed literary templates from his favourite writers, such as George Orwell, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.